Does wheat cause disease and obesity?

By Dr Friedrich Longin, University of Hohenheim

Bestsellers such as »Wheat Belly« or »The Grain Brain« set out to convince readers that eating wheat products is really bad. According to them, the grain makes you fat, age faster, be prone to dementia, diabetes and numerous other diseases. Their sole solution? To renounce wheat in the diet completely. Many consumers take this advice seriously with millions now following the no-wheat trend – above all in the USA and Australia, but also in Europe.

»Gluten free« is a huge trend

Nowadays, more and more people ask just how harmful wheat really is. After all, some of these books are written by doctors. The fact is that over 90% of humans profit from a diet containing a reasonable proportion of wheat wholemeal. This is confirmed in independent results from a very wide range of nutritional research organisations. Large-scale human trials also confirm that people consuming enough wholemeal cereal products (e.g. around two slices of bread daily) have much less risk of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory illnesses and similar ailments.

Basic foodstuff wheat

Globally, we realise there’s a big challenge ahead: a growing population must be fed from a decreasing area of farmland. Wheat joins rice and maize as the world’s most-grown crops. And there’s good reason for this because wheat’s cultivation requires relatively little water with approx. 900 l needed per kilogram grain produced. Compare this with the average 5000 l needed for a kilo of cheese. And even that’s nothing compared to the 20,000 l required for 1 kg of coffee beans. On top of this, wheat grain is comparatively is easy to store. And the staple food bread can be simply created from just wheat flour and water.

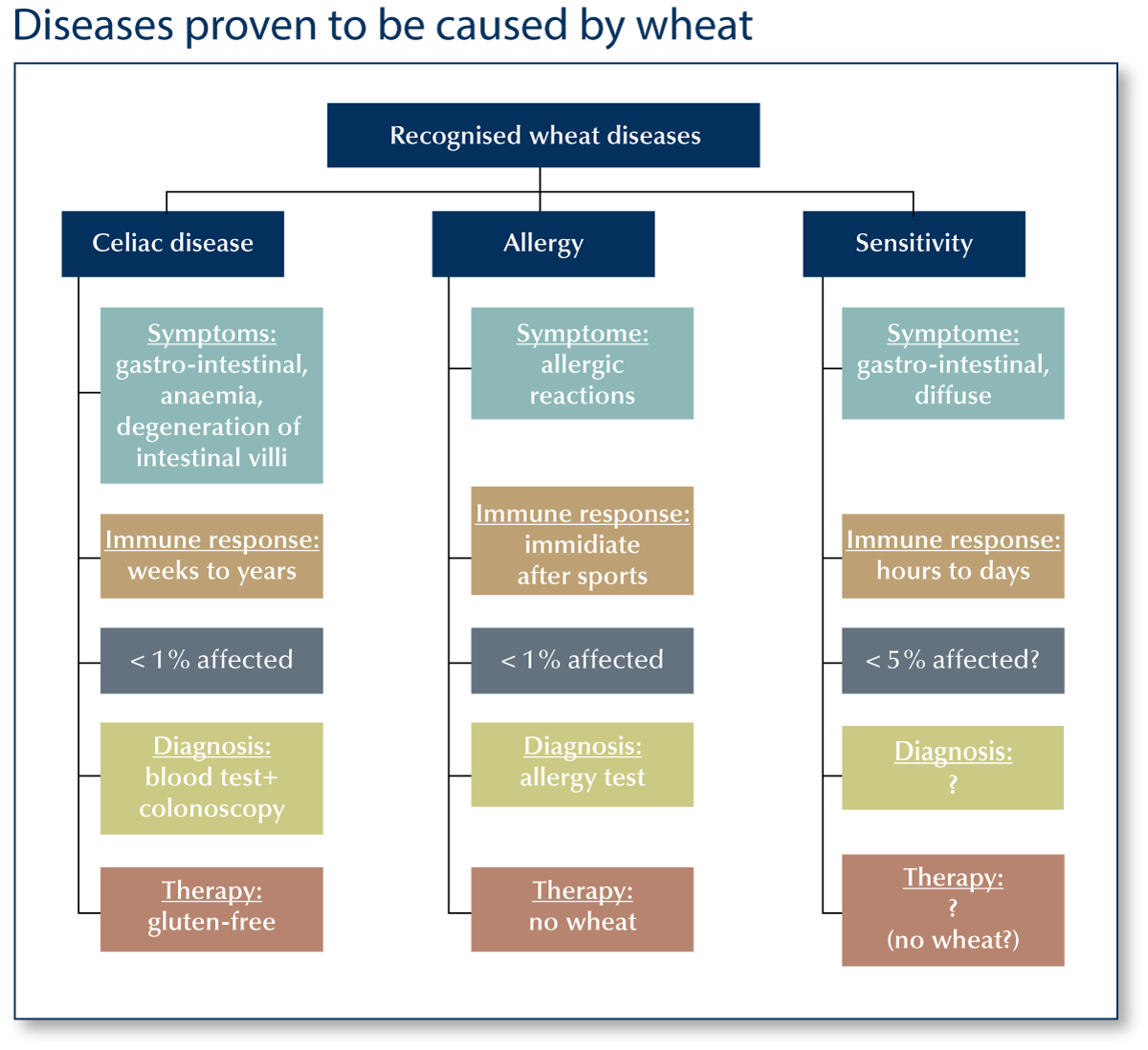

Only very few suffer from wheat-linked diseases

There are three scientifically-recognised diseases that can be caused through dietary wheat:

1. Celiac disease

Best known is the possible reaction to gluten, an important component of wheat grain. There’s no doubt that gluten influences incidence of celiac disease which is an inherited autoimmune disorder that leads to a chronic condition of the small intestine. This features lifelong oversensitivity to gluten and is present in approx. 0.5 to 1% of the population. Classic symptoms are gastro-intestinal problems, deficiency symptoms and tiredness. Mostly, the diagnosis is obvious. Where specialised blood tests prove positive, a colonoscopy follows. Patients with celiac disease have a greatly reduced number of, and less characteristically formed, intestinal villi. This leads to the symptoms. If the diagnosis is clearly celiac disease there is only one therapy – a lifelong gluten-free diet which, in effect, means less than 20 mg gluten may be consumed daily. This amount represents a cubic cm of bread. Scientists are currently testing whether oats might cause celiac disease. So far, the answer tends to be »no«. However, patients should wait a little longer for definite results in this case.

2. Wheat allergy

Here there are two different characteristic forms. But typical allergy symptoms through to anaphylactic shock are attributable to both. For some, wheat allergy emerges only in association with sport activities. The wheat allergy is caused by different wheat proteins. However, less than 1% of the population are affected in this way. Classical allergy tests are available and therapy is straightforward: a lifetime avoiding allergy, e.g. diets with no wheat content.

3. Wheat sensitivity

Symptoms of wheat sensitivity are very diffuse: from gastro-intestinal problems over simply feeling unwell, through to tiredness and other signs. Companies that produce products with spelt flour are also often involved in these discussions because, repeatedly, customers that report problems following consumption of wheat products claim these are less marked when spelt is used instead of wheat. So far, it hasn’t been clarified exactly what is responsible for the sensitivity. There is therefore naturally no clear diagnosis technique. The classical approach starts with exclusion of food allergies, celiac disease and irritable colon syndrome. Then, it is tested if a wheat-free diet under medical supervision effectively reduces the symptoms. The lack of diagnostic techniques means that it’s difficult to arrive at precise figures for this disease. Expert estimates run between 0.5 and 8% of the population. Neither is there clarity regarding therapy. Alone a reduction in wheat consumption appears to be effective. But does this apply only to soft wheat? Again, the picture is unclear.

Possible causes of wheat sensitivity:

- Amylase-Trypsin Inhibitors (ATI)

Science investigates several hypotheses on cause of wheat sensitivity. One is that Amylase-Trypsin Inhibitors (ATI) could be triggers for this sensitivity. ATI are proteins naturally occurring in wheat and other raw materials. They are believed to intensify already present inflammatory diseases, while having no effect where people are in good health. Apparently, there could be a genetic predisposition here. Only a small percentage of the population is affected. But findings so far are based only on trial results from cell cultures and animal experiments. Studies with humans are still ongoing. First claims that newer soft wheats contain more ATI than old wheat types such as einkorn, are scientifically unsupportable. In fact, there exist varietal differences in soft wheat ATI content that are caused by genetic influence, but also strongly influenced by the growing environment. The environmental effect is not surprising because, after all, ATI are wheat grain proteins and it is well known that protein content is very dependent on cultivation locality, plant variety and fertiliser application.

- FODMAPs: what are they?

One hypothesis is that wheat sensitivity is based on a group of difficult-to-digest carbohydrates and polyvalent alcohols, the so-called FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo, Di- and Mono-saccharides And Polyols). This group is present in numerous food materials, including wheat.

The FODMAP content is especially high, however, in onions, beans and cabbage. In wheat, the most important FODMAPs are fructan and raffinose. These can be produced through the incomplete degradation of starch to glucose. Hereby, it should be emphasised that fructan is often described as positive, being trigger of the so-called prebiotic effect, often advertised for yoghurts, etc. Apparently, however, a small percentage of the population has a problem with digesting these FODMAPs. FODMAPs are partly absorbed in the small intestine, the remainder moving into the large intestine where fermentation takes place through the resident bacteria population. Where grain products are consumed, this process often produces flatulence and other gastro-intestinal problems. But scientific evidence that FODMAPs trigger wheat sensitivity is completely missing so far. However, it does appear that irritated bowel syndrome patients suffer a worsening of their condition through the presence of FODMAPs. It is estimated that up to 15% of the population have an irritated bowel problem, whereby most show symptoms, although no definite diagnosis results.

- Where are FODMAPs to be found?

First precise investigations indicate differences in FODMAP content of wholemeal flour from einkorn, durum, spelt and wheat. Einkorn appears to have the most FODMAPs, closely followed by wheat, spelt and durum. Emmer, in particular, has a statistically demonstrable smaller FODMAP content than wheat.

However, the manner of dough and bread preparation has a far greater influence on FODMAP content in the end product. Traditional longer periods of kneading and addition of yeast or sourdough lead to almost complete breakdown of FODMAPs. Nowadays, though, many bakeries wheat produce their breads in the shortest possible time, and without sourdough. Such modern baking techniques could also be a ground for the higher proportion of people with wheat sensitivity. When in doubt, it therefore pays to ask a baker how long his or her dough is left to rise before it is baked. The longer the rising period, the less the content of FODMAPs and acrylamide with therefore more room for positive contents. Also, an ever-increasing number of additives is involved, including pure gluten. Especially for wholemeal bread, where encouraging rising can be problematical, the baker will add highly purified gluten from wheat. For all these reasons, research into the area of wheat sensitivity is urgently required.

Limited real knowledge about wheat

The authors of »The Grain Brain« & Co make as good as no reference to the above diseases. Instead, the books concern themselves with numerous generalisations on obesity, diabetes and further diseases whereby hard facts are either minimal or completely missing.

A non-wheat diet alone won’t make you slimmer

The correlation »eat lots of wheat = become very fat« is wrong. In countries with the greatest consumption of wheat, Kazakhstan, Algeria and Iran, the proportion of population medically seen as obese is substantially smaller than in the USA or EU, where very much less wheat is eaten.

While wheat can certainly make the consumer fat, this is only in the way that all types of food can lead to overweight when more is consumed than required by the body. Reducing obesity by foregoing wheat in the diet, as reported by the bestseller authors, can be simply due to the reduced intake of carbohydrates, which is in fact a central component of almost all dieting (»low carb«), usually coupled to recommended increases in sport activities, and has, therefore, nothing directly to do with wheat.

Does wheat breeding produce harmful substances?

Another claim is that plant breeding encourages content of toxic materials in wheat. There’s no argument that plant breeding is behind many changes. Even the very first crop growers improved plants through selection. Modern wheat varieties are a good deal more resistant to disease and deliver increased yields under continuously changing climatic conditions. But new protein cannot be created by breeding. Instead, conventional breeding tries only to unite, through natural crossing and selection, positive characteristics from different lines into a new variety. It should also be pointed out here that worldwide there’s not a single genetically modified wheat variety in commercial production. Also, the gluten content of modern wheat varieties is less than that of older varieties and of »ancient wheats« such as einkorn or emmer.

Wheat has existed almost as long as humanity

It is often heard that in their evolution humans haven’t had time to adapt themselves and their digestion to cope with wheat, and that this is why people may become ill. This is completely wrong: wheat has been a central source of carbohydrate in our diets since the Neolithic revolution more than 11,000 years ago. And humans consumed wild wheats long before even then. Grain plant types were widespread in the savannahs of the fertile »half-moon« region, the cradle of agriculture and human civilisation. Talking of adaptation, we humans have been confronted with consumption of milk and dairy products over a substantially shorter period. And still very much shorter in evolutionary terms are adjustment times for tropical fruits or technically modified food such as fat or sugar reduced products.

Science supports wheat

The authors of »Wheat Belly« & Co. mix snippets of fact with their own interpretations and, often wrong, causal associations. Additionally, clear scientific information goes unmentioned or is wrongly interpreted. A serious problem with this populistic demonising of wheat is that it particularly damages the case for people who really are suffering from wheat-caused diseases. The approach taken by the bestsellers means those affected have less chance of being taken seriously in their daily life by society, medicine and gastronomy. The situation also leads to a surfeit of anxiety among many consumers about food in general and wheat products in particular. Happily, very few people suffer from any of the three scientifically-recognised wheat diseases and thus most can eat foods based on wheat with no worries. In fact, where wholemeal is used for the products, they are doing something positive for their health.

Five facts on gluten

1. Gluten is…..

a mix of proteins. It is present in all wheats, i.e. also in spelt, durum, emmer, einkorn and khorosan as well as the wheat brands Kamut and 2ab wheat. In a somewhat modified form, gluten is also found in rye, barley and oats.

2. Gluten is good for...

airy, fluffy, bakery products and al dente pasta. When water is added to flour the gluten creates a fine network during mixing. In this network starch grains are held so that they can combine with water. When dough »rises« (yeast or sourdough fermentation) this gluten-starch network also helps hold the air in the bakery product which in turn gives a loose and moist crumb. The baking quality of a flour is dependent on the amount and the composition of the gluten.

3. Gluten is in…

lots of products. For instance, beer, soya sauce, some confectionary, frozen convenience meals, soup concentrate and sauce cubes, some cold meats and sausages, and cosmetics too. Thus, doing without gluten is not at all easy.

4. Wheat needs gluten because…

it confers a whole range of product quality advantages for baking and pastries.

For the wheat grain itself, gluten mainly acts as a store for nitrogen compounds required during germination/sprouting.

5. Without gluten, slimming would …

be in fact more difficult. That a gluten-free diet helps in slimming is a further factually inaccurate claim. On the contrary, patients with celiac disease actually gain weight when switched to gluten-free products. This is because they are able once again to digest and metabolise all the nutrients from their diets. In fact, everyone would tend to gain weight if on a gluten-free diet, although for a completely different reason: gluten-free bakery products have usually higher fat and sugar contents and lower fibre to help compensate for the missing gluten.