Farmland formed by man

by Thomas Preuße

Polders. Normally, soil is seen as simply the basis for growing crops. But now and again in the Netherlands one gets the impression that soil is a special substrate widely adaptable for a range of requirements.

Today’s Flevoland province has been won completely from the sea. Since 1932, an enclosing dike has separated the former Zuidersee from the North Sea thus forming the freshwater Ijsselmeer. In the 1940s, the 40,000 ha northeast polder was created: a first step in creating large areas of new farmland. By 1968, the 97,000 ha Flevopolder had been established in two sections.

Planned were another 40,000 ha but criticism, mainly based on environmental concerns, meant this idea was shelved. While the impression of an »artificial landscape« was very strong 30 or 40 years ago, especially in the newer Flevopolder, nowadays visitors no longer realise at first glance that they are 5 m under sea level – although it’s still plain enough at second glance.

Planned countryside and selected settlers

Everything is a tick tidier than in the rest of the Netherlands, where neatness is anyway a national trait. All is very rational and functional. After all, the landscapes here emerged from the drawing board, planned and developed by government. The inhabitants were also selected through strict criteria. They were to represent the Dutch nation in origin and religion, through abilities and social competence. Before young farmers could move into this »Promised Land«, they and their families were systematically checked out by government inspectors. Are they good farmers? Is the house clean, finances in order – and are they socially committed?

Best production conditions

Awaiting those who triumphed in the selection procedure was fertile and calcareous soil in comparatively large and well drained fields. The adventure of building a completely new society, of making the best of new opportunities, could now begin. In time, the farm sizes, initially 12 to 48 ha, expanded to a standard 60 ha. Even that size is now history. However, still notable is the pioneer character of land and people. »Without the example of the polders and their farmers, Dutch agriculture would maybe not have achieved the great leap forward managed in the last 50 years«, points out agricultural journalist Egbert Jonkheer.

Dutch agriculture: Specialised and export oriented for over 150 years

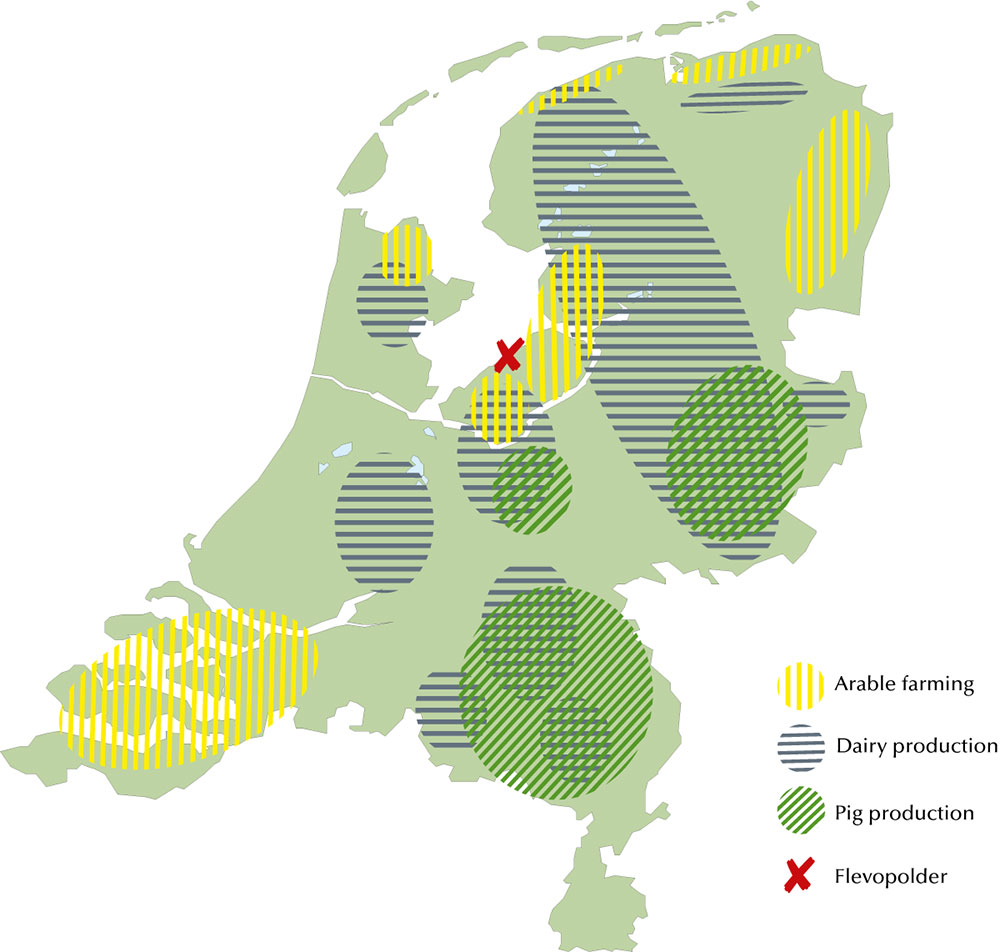

- Crop growing on the fertile marshland soils of the southwest,northeast and the polders;

- Dairy farming on the low-lying pasture regions in the middle of the country, in Friesland and in the east where soils tend to be sandy;

- Pig production, above all on the southeastern sandy soils.

Intensification as solution to limited farmland and massive urbanisation pressure Keyword for the future here is sustainability Limited space and urbanisation mean substantial structural change. While in 2000 there were still around 30,000 dairy farms with an average herd size of 50 cows, nowadays these farms have reduced to 17,000 with a mean herd of 95 cows. Thereby, the cow count has markedly increased since 2012. For pigs, total population remains fairly stable following a drastic reduction about 15 years ago. However, the number of pig producing farms has reduced from around 15000 in 2000 to 4500 currently, while pig numbers per farm have risen from an average 900 to nowadays 2800. Cost pressures are especially great with dairy farms with the most expensive factor being disposal of liquid manure.

Marked specialisation

Only 1200 farmers achieve two thirds or more of their turnover through crop growing. On average, these farms are small at just 42 ha. On the other hand, the proportion of high-value crops, those with increased financial risk, is large. The Netherlands is the largest exporter in the world of seed potatoes, onions and tulip bulbs.

The farmland area of around 500,000 ha comprises:

Potatoes: 157,446 ha of which: ware: 73,032 ha, starch: 43,146 ha, seed: 41,350 ha

Forage maize, with around 200,000 ha is the most-grown crop and is listed under forage area, which also includes around 1 m ha of temporary and permanent grassland.

Farmland prices exorbitant

Dutch average is 56 500 €/ha. In the polders, this rises to 80 000 and 120 000 €/ha. A tenant on state-owned land pays 1000 €/ha rent; other free tenants, 2 000 – 2 500 €/ha, and up to 4 000 €/ha for specialty crop land.

In the short term, the Rabobank, the largest agricultural bank in the Netherlands, sees a further separation between owning land and farming it, reports Egbert Jonkheer. Farmland renting in all its forms will play a greater role, as well as external investors and contract farming arrangements between crop growers and retiring farmers. This applies to dairy farmers too, because the expanding milk production farms need more feed and more land for disposal of manure.

Soil quality and health high on the agenda

In the past, large areas of farmland were too intensively cropped and are therefore no longer suitable for growing high-value produce such as potatoes, onions or tulips. Government and landowners both seek a system of land qualification as well as ways of persuading tenants to adopt more sustainable measures, for instance through required rates of compost application, catch crop growing or, more generally, establishment of a sustainability certificate. While voluntary exchange of farmland areas between neighbours is even now widespread, still more information is required in future about the soil involved. A concept that could be used here is a digital soil passport. This could give information on the nematode situation, or the plant protection materials used in preceding crops. So far, extensification isn’t being discussed. The first steps being taken involve technical solutions and more cooperation.