The agricultural sector in transition

By Henning Rabe, PHAEN Agtech, Kiel

What has worked well for a long time cannot suddenly be wrong? A supposedly proven principle is also widespread in the agricultural sector: Functional optimisation. With it comes the hour of the engineers and software engineers in technology companies. The hour of farm successors with an affinity for technology and new software-supported agricultural processes. Both are concerned with making better what has always been done before.

Doing it better, yes, but differently?

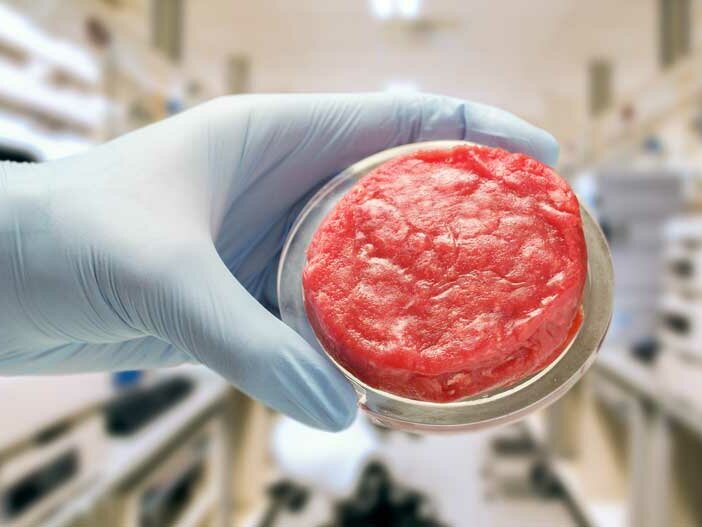

Companies have recently come onto the market with "cultivated meat", i.e. meat from the fermenter. We call it a meat substitute - almost helplessly, because you can't have what you can't have. The international researchers and pioneers are more straightforward. They call it meat because it is biochemically meat and tastes like it. No one wants to talk barbecue Americans out of eating meat or to put it down - only the way to the barbecue and onto the plate should be different, more sustainable, cheaper and healthier. With 90 % less water and 70 % less energy consumption, protein provision is being thought about differently and done differently. By new players with new rules of the game. This is no longer functional optimisation, no longer "more animal welfare", no longer the question of whether one should really only eat the animal's tenderloin and not also offal ("nose-to-tail"'). This is an overarching process pattern change - in this area of meat production alone.

What is supposed to be bad about meat from the fermenter, from quasi-industrial plants?

Beer is produced in exactly the same way. Breweries are fermentation plants in small- or large-scale industrial design. Cultivated meat is similar in production. Biotechnology and fermenters and extruders are changing the way meat is made for the millions of burger patties, lasagne mince and large-scale kitchen soup patties around the world. This requires other ways of providing biomass, less feed grain, other varieties of protein crops. Immediately the question arises: Where then does the well-kept steak come from, which we, with all our understanding of industrially used meat products, do not want to do without? Here, too, there are drivers of substantial process pattern change like Allan Savory who should be listened to, whose approaches should be thought through and widely implemented.

"Functional optimisation" and "process pattern change"

These two terms need to be contrasted to understand where change can come from, what real change can mean and encompass.

In order to better understand both terms, we will now finally tell the story of 20 October 1968 - when Dick Fosbury jumped backwards over the bar at the Olympic Games in Mexico. It was the glimpse behind the bar that rewarded him with the gold medal. That was a while ago. But for anyone over 60 today, the "Fosbury flop" has become proverbial.

Dick Fosbury previously jumped "belly-down" using the traditional straddle technique. But he, like his competitors, increasingly jumped against the bar. Any optimisation in inrun and take-off was not enough. The end of a "process technique" became obvious, despite all efforts. But there was a parallel development, even if imperceptible at first: behind the bar, the world was changing. With the development of polyurethane in the sixties, the mats behind the bar became thicker and softer - so soft that for the first time there was no danger of breaking one's neck if it hit the mat first.

Seven drivers of change

- Digitisation: A broad field, a hackneyed topic. Yet extremely influential.

- Drive technology: Open-ended, but certainly not without e-drives.

- Supply chains and global dependencies: And then there are the current dramatic upheavals.

- Climate: Water scarcity and the consequences for arable farming and the supply of fodder: a different situation from year to year.

- Labour force: Lack of young agricultural professionals, no reputation, hardly any careers.

- Sustainability: Soil compaction, fertiliser, plant protection, breeding, genetic engineering.

- Cultivated food: Protein supply made new. Meat remains meat, but without detours: new players with their own rules.

What is inspiring for corporate strategists about Dick's remarkable lesson?

It is this: What to do in a situation where what has always worked no longer works? What to do when, despite immense effort, even the best "jumpers" in the company jump against the bar more and more often and market success fails to materialise? Perhaps it also fails to materialise because the bar has to be raised ever higher due to competition. This is not "disruption", the sudden end of a traditional business model. It is a creeping process - almost more perfidious than disruption, because the "It'll be alright!" creeps into the back of management's mind all too readily.

This realisation that with the change behind the bar, the processes in front of it could be designed completely differently benefited the person who had previously pulled the old process through to perfection a zillion times. No polyurethane developer had ever thought that his invention could revolutionise the high jump. No foam mat specialist stood on the sports field and talked about a different run-up, about turning and jumping backwards. Dick came up with it himself because he realised that something else was possible. Before every process pattern change, you need this realisation that the world changes behind the bar.

How long can it take for successful process pattern changes to really take hold?

For the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, the famous designer Otl Aicher still developed the old "roll forward" in his icon library for the high jump. But the women's gold medal went to a young innovator of the new technology, Ulrike Meyfarth. Won with Fosbury flop in competition with older top female jumpers who preferred the straddle technique. Ten years later, Ulrike Meyfarth again optimised the Fosbury flop in such a way that a height increase of 11 cm became possible. To 2.03 m, her best performance.

Two messages as a conclusion

Process pattern change starts with looking to see if the world changes behind the bar. These new processes then go through meaningful steps of optimising functions again. For market participants, for manufacturers as well as for users, it is this parallelism that must be endured.

- In phases of function optimisation, money is earned until it is no longer profitable.

- In phases of process pattern change, money has to be invested and you pay for it.

It only becomes lucrative again when the functions are optimised again. Those who don't get involved, who push the optimisation of previous processes to the limit, don't realise how much the world has already changed behind the bar.